I have seen some confusions recently on twitter regarding university finances. Here are four recommendations:

- Avoid using sector aggregate figures to make your arguments

The sector is very uneven both in terms of size of institutions and in financial performance, make sure you are familiar with your institution and how it fits into the sector. - Avoid using figures for “reserves” when you mean cash

In accounting terms, “reserves” does not mean cash. Cash is included in reserves but that is because reserves names the excess of assets over liabilities: that the institution owns more than it owes. If it didn’t have reserves it would be insolvent. But its assets include buildings and land, which can dominate the reserves figure.

It is a confusion that crops up regularly and is often associated with right-wing arguments about the sector being “awash with cash”. If you want to talk about cash, use the figures for cash – but bear in mind that it is good management to hold significant levels of cash or other liquid assets to manage the day-to-day running of the organisation. Universities are large and have large outgoings! - Revolving Credit Facilities (RCFs) are like overdrafts …

If you have one, you aren’t necessarily planning to use it.

It provides extra headroom or is there for an emergency. Universities might simply be using it in their “liquidity” calculations to assure OfS that they have sufficient resources to cover 30 days of expenditure – falling below that level is a “reportable event” – and never intend to use it.

That your institution negotiated one, but haven’t used it, is not per se a sign of bad management. - Avoid confusing one-off costs with recurrent costs

There is a clear difference between spending £1million on a one-off purchase and an annual outgoing of £1million.

Your management may not always present the difference between such items in a very clear way, particularly when they have a certain narrative they wish to present or when they need to hit targets or covenants.

One to be wary of is “vacancy savings”. Are these higher because of a recruitment freeze? Are these one-offs or recurrent savings? Technically, the former; they would only become recurrent savings, if the posts are made redundant.

A management highlighting a certain level of vacancy savings may want to convey discipline to governors or lenders, but it can mask issues of sustainability: it isn’t a way to address persistent deficits. If there is an underlying deficit of, say, £2million, you shouldn’t be confident because they covered that through a recruitment freeze this year. And that’s solely from the numbers perspective: before you consider the implications for workload …

There are a few resources on this site for thinking about university finances. There is also a blog and recorded seminar for UCU on getting started with university accounts and “challenging the financial narrative”.

If you want more help, please get in touch.

I have worked with more than 40 UCU branches over the last few years to help with negotiations. Get in touch for details.

A testimonial:

With the Comprehensive Spending Review due next Wednesday, I thought it might be worth making some general points about student loans (in anticipation of potential changes to repayment thresholds and other parameters).

I do not think student loans are a good vehicle for redistributive measures.

As I told a couple of parliamentary committees in 2017, the current redistributive aspects are an accidental function of the decision to lower the financial reporting discount rate for student loans from RPI plus 2.2 percent to RPI plus 0.7. Such a downwards revision elevates the value of future cash repayments and in this case it meant that the payments projected to be received from higher earners began to exceed the value of the initial cash outlay.

The caveat here: in the eyes of government. That is the government’s discount rate, not necessarily yours. One of the reasons I favour zero real interest rates over other options is that it simplifies considerations of the future value of payments made from the individual borrower’s perspective.

Originally, student loans were proposed as a way to eliminate a middle class subsidy – free tuition – and have now become embedded as a way to fund mass, but not universal, provision.

I believe that if you are concerned about redistribution, then it is best to concentrate on the broader tax system, rather than focusing solely on the progressivity or otherwise of student loans. You can see from the original designs for the 2012 changes that the idea of the higher interest rates were meant to make the loan scheme mimic a proportionate graduate tax and eliminate the interest rate subsidy enjoyed by higher earners on older loans. The original choice of “post-2012” student loan interest rates of RPI + 0 to 3 percentage points was meant to match roughly the old discount rate of RPI plus 2.2%. Again, see my submission to the Treasury select committee for more detail.

I will just set out a few illustrative examples here as to why some of the debates about fairness in relation to repayment terms need a broader lens.

It is often observed that two graduates on the same salaries are left with different disposable incomes, if one has benefited from their parents, say, paying their tuition fees and costs of living during study so that they don’t lose 9 per cent of their salary over the repayment threshold (just under £20,000 per year for pre-2012 loans; just over £27,000 for post-2012 loans).

That’s clearly the case.

But the parents had to pay c. £50,000 upfront to gain that benefit for their child. And it is by no means certain that option is the best use of such available money. Only a minority of borrowers go on to repay the equivalent of what they borrowed using the government’s discount rate, and as an individual you should probably have a higher discount rate than the government. You also forego the built-in death and disability insurance in student loans.

Payment upfront is therefore a gamble, one where the odds differ markedly for men and women. (See analyses by London Economics and Institute for Fiscal Affairs for the breakdowns on the different percentages of men and women who do pay the equivalent of more than they borrowed.)

If a family has the £50,000 spare (certainly don’t borrow it from elsewhere), then the following options are likely more sensible:

- pledge to cover your child’s rent until the £50,000 runs out: this allows student to avoid taking on excessive paid work during study and will boost their disposable income afterwards;

- provide the £50,000 as a deposit towards a house purchase;

- even put the £50,000 in a pot to cover the student loan repayments as they arise;

- etc.

In two of those cases, you’ll have a useful contingency fund too.

All strike me as better options than eschewing the government-subsidised loan scheme.

Moreover, those three options remain in the event of a graduate tax or the abolition of tuition fees.

That fundamental unfairness – family wealth – isn’t addressed by changing the HE funding system. (I write as someone who helped craft the HE pledges in Labour’s 2015 and 2017 manifestos).

In many ways, the government prefers people to pay upfront because it reduces the immediate cash demand. From that perspective, upfront payment works as a form of voluntary wealth taxation (at least in the short-run). Arguably, those who pay upfront have been taxed at the beginning and are gambling on outcomes that mean that future “rebates” exceed the original payment for their children.

Perhaps this line of reasoning opens up debates about means-testing fees and emphasises the need to restore maintenance grants … but really it points to harder problems regarding the taxation of intergenerational transfers and disposable wealth.

I am not a certified financial advisor so comments above are simply my opinions. You should not base investment decisions on them.

Why that title?

Well, the name seems to mislead people into thinking that the provider of student finance is a private institution, potentially making profit out of students, when it is in fact publicly owned.

There are 20 shares in the SLC: 17 are owned by the Department for Education (which has responsibility for English-domiciled students) and another three, each of those owned by one of the devolved administrations.

When you want to see what’s going on with student loans you look at government accounts: national, departmental or those of devolved administrations.

OK. So what’s the point of mentioning this factoid?

I believe that the misunderstanding about the publicly-owned nature of the SLC contributes to thinking that leads to other confusions, such as those surrounding function of the interest rate in student loans and what the effect of reducing them would be.

Here’s a former Higher Education minister getting into a pickle in an article that even has the title, “Student Finance? It’s the interest rate, stupid”.

Let’s leave aside the misunderstandings about the recent ONS accounting changes and concentrate on the claim that reducing interest rates would “address the size of the debt owed itself”.

The government is looking to reduce public debt, but lowering interest rates would only do this in the long-run, if the loan balances eventually written off were written off by making a payment to a private company to clear those balances.

As it is, reducing interest rates on loans mean that higher earners will pay back less than they would otherwise and government debt would be higher in nominal terms (all else being equal). (I do support reducing interest rates on student loans, but for different reasons).

There is probably another confusion here regarding the Janus-faced nature of student debt: it is an asset for government (it is owed to government) and a liability for borrowers. The outstanding balances on borrowers’ accounts are not the same as the associated government debt.

When the government thinks about public debt in relation to student loans, it is thinking about the borrowing it had to take on in order to create the student loans.

Imagine that I borrow £10 in the bond markets to lend you £10 for your studies: I have a debt to the markets and an asset, what you owe me. The interest on the former and the latter are not the same and the terms of repayment on the latter are income-contingent so I don’t expect to get sufficient repayments back from you to cover my debt to the markets.

Student loans are not self-sustaining. It requires a public subsidy – any announcements about loans in the spending review at the end of the month will be about how much subsidy the government is prepared to offer.

David Watson once wrote that the answer to the question as to whether universities were in the private or the public sector was “yes”.

He suggested that universities most resembled BAE Systems: a private company with a host of public contracts. Back in 2011, the Coalition white paper on HE opened by trumpeting “Higher education is a successful public-private partnership: Government funding and institutional autonomy.”

It was always the aim of second round of public sector reform (“Privatisation 2.0”) to create an education market that could be regulated like public utilities in the UK. And so the recent spate of collapses amongst energy “suppliers” prompted me to think about Watson’s comments through the lens of bankruptcy.

The measures taken by the regulator, Ofgem, reminded me that the government has pledged to take a similar approach to university “failure”.

Last summer’s announcement from the Department for Education of an HE “Restructuring Regime” (HERR) was badged as a Covid-related, “last resort” and outlined general principles covering possible government support pre-bankruptcy.

Consistent with earlier statements regarding its approach to the orderly exit of “unviable institutions”, the opening sections of the HERR made things clear:

§4 The Regime does not represent a taxpayer-funded bail-out of the individual organisations which make up the higher education sector. It is not a guarantee that no organisation will fail – though current students would be supported to complete their studies, either at that institution or another.

Providers approaching DfE for support will be considered on a case-by-case basis, to ensure that there is a sound economic case for government intervention, with loans to support restructuring coming from public funds as a last resort.

A precedent here can be seen in the “Task Force” established in 2012 when the government rescinded London Metropolitan’s right to sponsor international students.

There, a “clearing house” was even established to distribute around 2000 affected students to alternative courses at different providers.

HERR made the priorities clear for its case by case consideration of whether to lend to an institution that had exhausted all other options and ‘would otherwise exit the market’:

- the interests of students;

- value for money;

- maintenance of a strong science base;

- alignment with regional economies;

- support for “high quality courses aligned with economic and societal needs”.

Elaborating on the last of those, the 2020 document unsurprisingly picked out “STEM, nursing and teaching”. In sum, an institution in difficulties would be required to show that:

(i) it had a plan for future sustainability;

and (ii) that its collapse ‘would cause significant harm to the national or local economy or society’.

Alongside those points, it is worth recognising that it will be easier for the government to be sanguine about the disappearance of smaller institutions in areas that are otherwise well covered by universities (e.g. London).

Those that would be offered help will still find the “Regime” a deeply unpleasant experience: they mean it when the write about a “last resort”.

A bankrupt university will prove a bigger problem than an energy provider. But it is clear that the government will aim along those lines, such that a university bankruptcy will not be like a local authority issuing a “section 114”.

One should therefore reject any idea that financial deficits do not matter for universities.

Like private companies they face cash constraints. They can support an excess of expenditure over income so long as the cash outflow can be absorbed by cash reserves. When the latter are exhausted and debts cannot be settled as they fall due, then the institution will fall over without outside support.

Popular critiques of austerity and theories about governments and money might have misled people here.

Governments are not like households, but universities are, insofar as they need to generate more income than they spend.

As Watson noted, his answer about BAE Systems would make a lot of people uncomfortable. It’s even more discomforting to think that the government might view universities more like Igloo, Symbio, Enstroga et. al..

UPDATE – 7th October

By coincidence, DfE has just announced the closure of the “Regime” to “new applicants” with a deadline of 31 December 2021. They aim to move all applications “to a conclusion” by July 2022.

This decision reflects the fact that HERR was a pandemic measure, but, as I outlined above, the process and criteria set out there do give some indications as to how the department and regulatory bodies will approach bankruptcies in general.

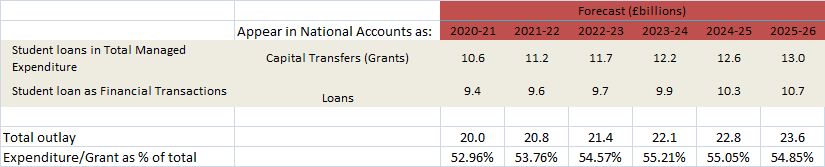

I have constructed the table above from forecasts for Total Managed Expenditure and Financial Transactions taken from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility’s latest publication (it accompanied Wednesday’s Budget).

It shows how newly issued student loans are now split into two components for the purposes of presentation in the National Accounts. The portion of loans that are expected to be repaid are classed as “financial transactions”, while the portion expected to be written off is recorded as capital expenditure. The latter scores in “public sector investment”, which was adopted as a new fiscal target prior to the pandemic (net investment cannot exceed 3% of national income), though the rules are currently under review.

We can see that student loan outlay is expected to reach £20billion in the year to March 2021, rising to £23.6billion in five years’ time.

The majority of new outlay is now expected to be written off and that share rises over the forecast period.

By 2025/26 repayments on all existing loans are projected to re000000000000000ach nearly £5billion per year. (This figure has improved since the sale programme for post-2012 loans was abandoned, since the treasury now gets the receipts that would have gone to private purchasers).

As mentioned in recent posts on here, the Department for Education only currently has an allocation of £4billion to cover the capital transfer / grant element of new loans and so it has to be granted large additional budgetary supplements each year. This situation has dragged on as the planned spending review has been postponed. We can now expect developments in the Autumn.

Last week’s Supplementary Estimates contained another note of interest for student loans.

Under “Note K: Contingent Liabilities” (p. 90) we find that a fifth contingent liability has been added to those associated with the now abandoned sale of student loans.

The sale of student loans necessitated warranties and indemnities to secure interest and obtain value

for money from investors. These contingent liabilities are in respect of:…

e) New EU Securitisation Regulations (Possible CL [contingent liability] in due course). UKGI [UK Government and Investment] are seeking legal counsel to review the implications of new EU securitisation reporting requirements from 2019. Credit granting criteria are being assessed for student loans which may generate legal challenge and we will continue to work with UKGI to update as more information and analysis becomes available.

If any reader can explain what the issues may be here, I would be very grateful.

The original four contingent liabilities are discussed here. These, along with the fifth, are still classed as “unquantifiable”.

There were also issues around whether the Special Purpose Vehicles for the securitisations were sufficiently independent of government so as to constitute a genuine sale (and thereby transfer the loans off the government’s balance sheet).

The wording above though suggests that the lack of “credit” checks on student loans may be the issue.

The UK government published its “supplementary estimates” for 2020/21 yesterday. These allocate additional budgetary resources to departments.

Education has been given an extra £13.531 billion to cover the estimated losses on student loans issued in the year (April 2020-March 2021) and the likely downwards revisions to the value of already existing loans. The department had an original allowance of roughly £4billion, but was determined by the last comprehensive spending review and had not been revised since Theresa May’s decision to increase the loan repayment threshold in 2017.

Last year, an additional £12billion was granted and most was used. (These allocations are not additional cash, but the formal recognition that the cash issued in the form of loans is going to generate much lower returns than originally anticipated).

The estimated non-repayment on new loans was thought to be in the region of 55%. That is, for every £ loaned, the treasury expected the equivalent of c. 45p in return: in 2019/20, £17.6billion of new loans were issued, but only around £8billion in net present value is projected to be repaid. (Note that this percentage figure – “the RAB” – is often confused with a measure of how many borrowers ultimately clear their loan balances, i.e. those who repay the equivalent of 100p or more).

When the new higher fees came in, the loss on loans was projected to be in the region of 30p in the £. That is, 70p would be repaid. A raft of policy changes and modelling errors along with the impact of austerity on graduate earnings has dramatically increased the costs; recent accounting changes have meant that those costs now show up in the headline figures that count. (The loan scheme was never designed to be self-financing, but no one set out to develop a scheme with this current level of subsidy. The £4billion in the original budget for 2020/21 reflects the much earlier aim of “incentivising” the department responsible for loans to get the estimated non-repayment closer to 30-35%).

The pandemic has made things a lot worse for earnings and livelihoods. But the HE sector has in recent months also been positioned to take a hit when the chancellor looks to review spending in the Autumn. The obvious place to look is initial outlay and so I would expect to a clamp down on undergraduate fee levels (without any offsetting increase in tuition grant).

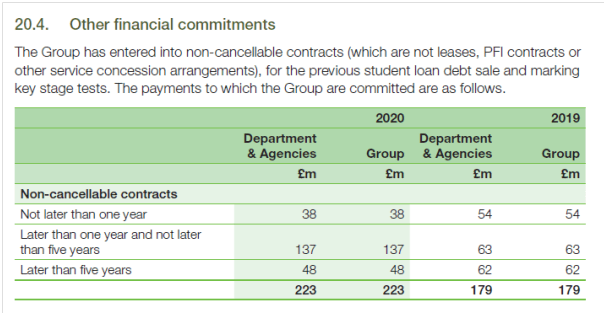

Page 221 of the Department for Education’s 2019/20 financial statement contains the note reproduced above.

The sale programme for “pre-2012” student loans was cancelled in March. But DfE looks like it will be paying out over £30million per year for the next few years to financiers anyway. Total liabilities are booked above at over £220million.

Given the relative absence of higher education from yesterday’s Autumn Statement, I turned my attention to the Department for Education’s 2019/20 annual accounts, which were published earlier this month.

Regarding student loans, we have been in something of a hiatus since 2018, when Theresa May announced an review of post-18 funding and commissioned the Augar panel, which reported last summer. Although there were suggestions that we might get a long overdue response to the latter yesterday, we will probably have to wait now until the Budget next March, when the government will hope to have a better sense of its spending commitments.

That leaves student loan finance in limbo with the small, nominal budget allocation for loan write-offs shored up by large “Supplementary Estimates” provided by parliament each February.

This is in spite of an apparent “target RAB” of 36% and a budgeting process hanging over from 2014, when the old department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) had responsibility for loans and was being “incentivised” to reduce the cost of the loan scheme. You can see both of these features still stipulated in the latest Consolidated Budgeting Guidance, but they represent zombie policy with little to no bearing on events.

Why so? Well, DfE was given an extra £12billion plus back in February to supplement 2019/20’s budget for “non-cash RDEL” (mostly student loan “impairments”) of £4.7billion per year. (Student loans are “impaired” because the loans are worth less in estimated repayments than the cash advanced.) The supplement produces a total that is more than triple the original allocation.

And… DfE managed to spend nearly £16billion of that last year. The accounts report an “underspend” of £1.1bn against that total.

As can be seen from the table below, “Fair Value movement” for student loans amounted to a non-cash cost of over £14billion.

£17.6billion of new loans were issued, a net increase of £15billion once repayments of over £2billion are considered, but the new impairments on post-2012 loans increased by £12.3billion; for “pre-2012” loans the stock remaining at year-end lost nearly £1.7bn when revalued.

Although the nominal value (“face value”) of outstanding post-2012 loan balances is nearly £105billion, those loans are thought to be worth less than £50bn.

Read more…